It only takes a spark...

A story about my failures and my learning in teaching students in CHC2P for the blog series: Hindsight 2020.

Originally published as part of Write-On, the 2016 Ontario summer literacy symposium, also published on the OHASSTA website

It was hard to believe that they were the same students.

Phones were put away (mostly), eye contact occurred between students whose heads were together in intense and sometimes spirited discussions about rural life in 1950s Quebec society.

“Why did he just go to church and pray?”

“I would’ve been so angry, I would just burn the sweater!”

“Why didn’t he just send it back and get a new one?”

“Who was the minority? Was it the francophones or the anglophones?”

***

The week before, Kim had been trying to get these same students working together. The desks were in groups and had been all semester. She had grouped according to the learning needs of particular activities, accounting for reading ability, first language, interests, ability to stay on task and social skills. Her lessons were interesting, relatable topics and she spent lots of time preparing, giving feedback on assignments and getting to know her students as individuals. But when she had them in small groups, she felt like she was putting out fires with an eyedropper. Every time she would finish helping one group, they would stop “working” until she came back. With a class of 28 students, all of whom had a wide variety of academic challenges, sometimes she could only work with a group once in a class period. Did these grade 10 students really ALL need that much personal attention? Why couldn’t they stay on task and work together?

The more capable students would often ask more questions, so the ones who really needed help were getting less of it because she didn’t always have the energy to work with them to get them to start. How could she get them to want to learn? How could she meet all of their needs and cover some semblance of the curriculum?

***

Was this the same group of students one week later? What was going on here?

***

Maybe you have felt like Kim. I know I have. A few years ago, I had the same kind of class. I had developed interesting materials that I thought my students could connect with, I knew all their needs, had grouped them accordingly, but despite putting out a million fires, it still seemed like the spark was missing. My students were learning at a snail’s pace, or not learning anything at all. I knew that there was something that each of them was interested in, or got excited about, but it never seemed to translate to a consistent classroom effort or productive work in small groups. I needed to figure out how to get my students to want to learn, to spark them to self-motivation.

A group of my colleagues sat in my classroom with this difficult class and observed what they were learning (or really, not learning) while I delivered a lesson that we had co-planned. This lesson was amazing, we had laminated primary source documents – photographs and letters, we had a great introductory activity about discrimination, and we had organizers for the students to complete together that we hoped would engage them in the activity, and get them asking lots of higher-order questions. It was supposed to be a fantastic lesson!

What happened? The introductory activity got them thinking, and I was especially pleased to see one student who rarely participated really ask some great questions about a historical photograph in the large group setting. Then each small group was assigned a very short document to read through and analyze. The idea was that they would then jigsaw and put together the bigger picture of all the documents.

Total failure. I was, as usual, running around from group to group, helping them to decode the text. My colleagues reported that all the conversations when I wasn’t there were about the weekend, or parties, or who liked who, and other social conversations. Even though the teacher was sitting right by them, they seemed oblivious to things like appropriate classroom language or discussions about illegal activities or just blatant use of their cell phones to play games or text their friends.

I was devastated. My peers had witnessed what a terrible disciplinarian I was, and how group work was a failure. I had been hoping to encourage them to try more group work in their classes, but it appeared that I had likely discouraged them!

But then, something happened in the debrief session right after the lesson. My colleagues had also observed that the students didn’t seem to be able to decode the primary source documents because they just couldn’t read very well. Their reading comprehension of even the instructions and the non-primary source texts was very low. They were very capable of generating amazing questions when given a visual prompt, but the questions stopped, and the engagement stopped when they were trying to read the texts. And then they just waited for me to come around and read it to them, or explain it to them. They weren’t being lazy or obstinate. They just couldn’t READ!

That changed my point of view entirely about that class, and about my career. My job as a teacher shifted from focusing on my teaching to focus on my students’ learning. My job was not to develop the best lesson and teach it, my job was now to help my students learn so that they can be successful and productive adults in the world. I had taught for 16 years without fully understanding this fundamental truth of our profession.

In that class, I started by using more visual and video primary sources (photographs, news pieces, drawings, maps) to have students practice analyzing historical texts. I selected even shorter text documents and we read them aloud together, or I paired the weaker students with stronger readers to work together. It was far from perfect, but the students started sparking and learning. They were creating the right kind of fires within themselves.

My experience with that class showed me how few appropriate resources were available to history teachers who wanted to have students engage with primary sources, especially students who struggle with literacy. Primary sources are difficult even for good readers, but I was beginning to see how to get students who were struggling with literacy to be able to understand and analyze them. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to co-author a textbook, History Uncovered, for use with students in grade 10 Applied and ESL history classes. My students were ever in my mind as I was conceptualizing, writing, revising and re-revising that resource.

Through three more planning sessions, observation, and reflective sessions in my colleagues’ classes, we learned more together about how to spark students, so that we don’t have to put out fires. We put our collective experience and imagination together and came up with some really engaging activities to help students develop their own inquiry questions.

We used a lot of sticky notes and chart paper, whiteboards and markers; we had students moving around the room, ranking each others questions, and we gave them the confidence and the opportunity to be their own guides in their own learning. We listened to our students talking, and through listening, I learned that I really can trust my students to talk productively and to work together to solve problems. Sometimes they needed better materials, sometimes they needed more time, sometimes they needed more help, but often they needed less help. Mostly what they needed was for me to say less, to listen more and to help with the real problems when they did come up. I put out fewer fires, and they started to spark and glow.

****

The same process had unfolded in Kim’s class. It was again through intentional collaboration with a group of colleagues, focused on a goal, and supported by the principal and the school learning plan.

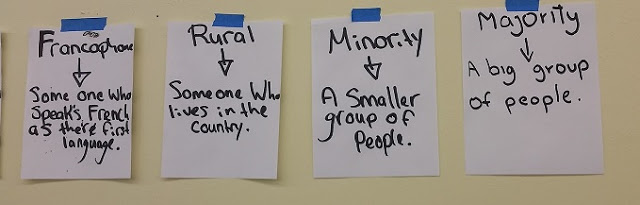

We planned together, observed, reflected, and planned again. What was Kim’s realization? Her students, most of whom were English Language Learners, just didn’t have much vocabulary. We expected that they might not know words like anglophone and francophone, but we were surprised that they didn’t know words like “minority.” We were initially trying to have the students follow a reciprocal teaching protocol but it was not as effective in that class as in the others we had observed, they were probably not ready, or needed more practice with the complex protocol.

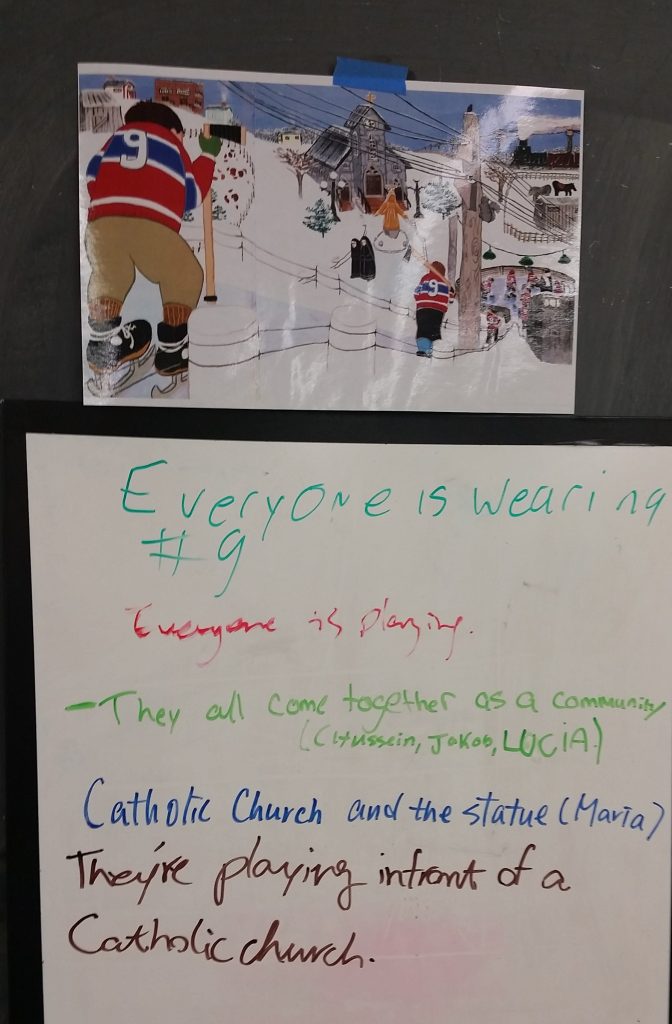

What was effective, was the preparatory work that Kim had done before we observed. She had her students do a predictive activity with images from the picture-book version of The Hockey Sweater (Roch Carrier, 1979) and create a word wall with pre-selected vocabulary. They looked up the definitions and wrote them down, and the legible ones were posted on the wall. For the next two weeks, as the students learned more about Quebec culture and the October Crisis of 1970, they constantly referred to the word wall to explain their thoughts to their peers, to write, and to read.

The Hockey Sweater lesson was not developed by our group alone. It was developed by another group of teachers at another school as part of an ELL network. The collaboration was not just in our little group at one school but was across schools. This is exactly the kind of impact that I had hoped to have as a coach. To be able to set the conditions so that teachers like Kim could see their students a little differently and be able to see their colleagues as co-learners, to see their work differently, and to find new joy, hope, and purpose in it. To start to discover answers to some of the problems that plague us in this most complex of professions.

Resources to share:

The Hockey Sweater Lesson

- Student Handout – The Hockey Sweater

- Images from the storybook

- Hockey Sweater vocabulary to cut out (optional)

The Avro Arrow Lesson

- This was to prepare students to read and respond to this document set from the Begbie Contest.

- Student Handout – The Avro Arrow

- Word Wall – match definitions

The October Crisis Lesson

- Student Handout – The October Crisis

- Word Wall – vocabulary and definitions

*Note: We did the word wall differently in each activity, some in the interests of time, but it seemed to be most effective when students looked up and wrote down the definitions themselves, though many spirited discussions were also had during the matching activities.

Comments

Post a Comment